NON-REDUCING

Introduction

Compared to other traditional polyphasic schedules with the added benefit of reducing the hours spent in bed each day, polyphasic lifestyles with no reduction in total sleep have been around for a very long time.

- Segmented sleep in the pre-industrial era features a normal amount of sleep that adds up to the total amount of sleep in monophasic sleep today1.

- Certain medical students also slept biphasically without reducing their total sleep2.

- Currently, non-reducing polyphasic schedules exist in the forms of:

- Biphasic sleep

- Multiple sleeps per day

- Random sleep schedules that involve more than one sleep each day.

Total sleep of all these variants is equivalent to that of monophasic sleep.

For clarification, reducing schedules refer to any sleep schedules that reduce the amount of time spent in bed in comparison with personal monophasic sleep need.

Content

- Mechanism

- Non-reducing Biphasic Sleep

- Non-reducing Polyphasic Sleep

- Random Sleep

- Comparison between Non-reducing and Reducing Schedules

Overall Mechanism

The clear cut mechanism of this sleeping scheme is currently not entirely clear. Polyphasic principles that apply to other traditional schedules may or may not apply to non-reducing polyphasic schedules.

Common rules regarding diet and lifestyle may also be different for non-reducing polyphasic schedules. However, main ideas such as repartitioning and compression of sleep can still be applicable in some schedules.

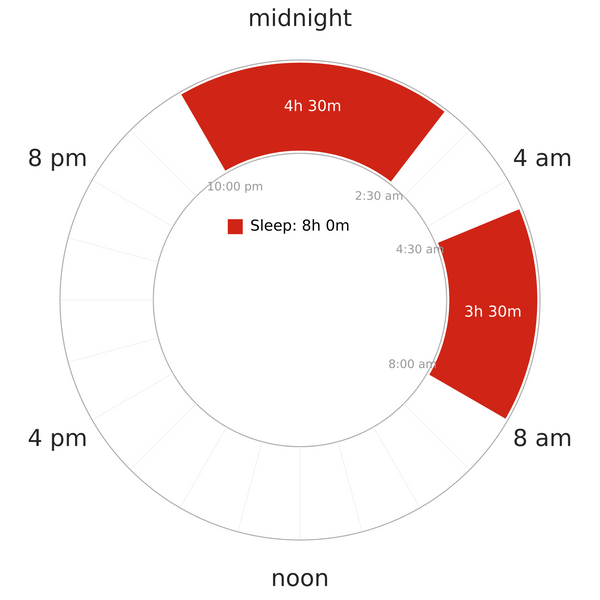

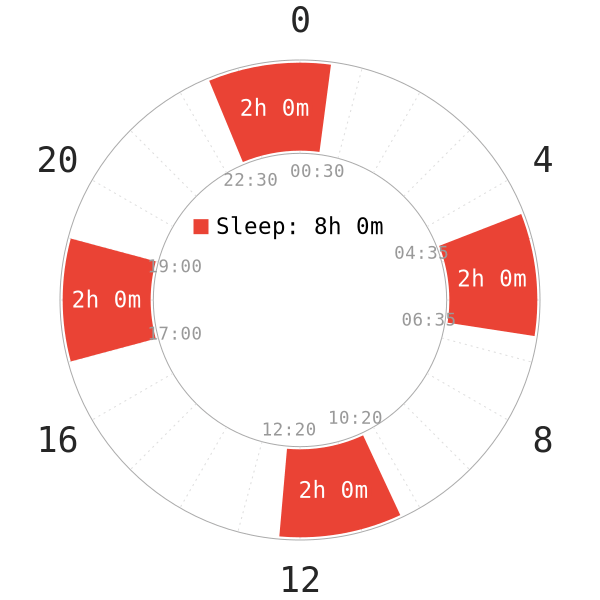

- A sleeper who is monophasic for their life will still need an adaptation to a non-reducing sleep pattern. This is the case if its structure is vastly different from monophasic. Such examples include 3 core sleeps of 2h40m (8 hours total sleep as Triphasic-extended), 4 core sleeps of 2 hours, 2 core sleeps of 4 hours (8 hours sleep total as Segmented sleep), etc.

- However, the adaptation process is overall much easier. This is because sleep deprivation as a primary stimulus is nowhere near that of other reducing schedules.

- Entirely random polyphasic schedules that have no definite shape or form theoretically require no adaptation at all. It is impossible to adapt as well. This is because there are no records of anyone managing to adapt to alternating schedules.

- Due to the erratic and self-fulfilling nature of random schedules, the body will wake up on its own in the last sleep of the day with a sufficient amount of SWS and REM from previous sleep(s). Check unadvisable schedules for more information.

NON-REDUCING BIPHASIC SLEEP

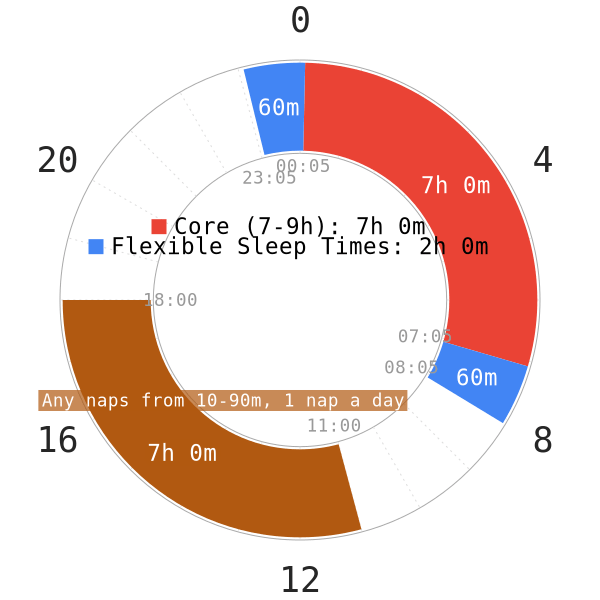

BIPHASIC-X

- Proposed by: GeneralNguyen

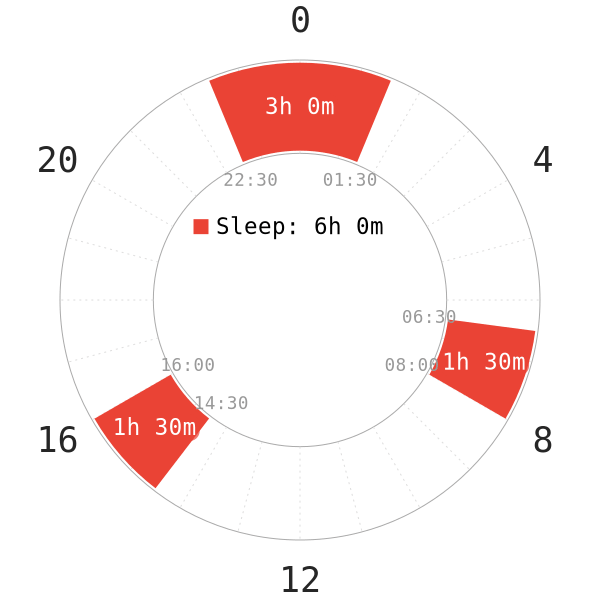

- Total sleep: ~7-9 hours (depending on individual monophasic sleep need)

- Classification: Biphasic, Flexible, Non-reducing Polyphasic Sleep

- Specification: 1 long core sleep, naps with varying lengths or consistent length depending on days, NREM1/NREM2 nap if duration is short (< ~25-30m), contains SWS/REM if duration is longer (> 60m)

- Mechanics: 1 core sleep, 1 nap as main form. More than 1 core sleep or 1 nap (reduce total sleep) is allowed on busier days. Recovery day is done afterwards to recover from sleep deprivation (increase total sleep by extending either core length or nap length in Biphasic form) to keep up napping habits. Both core sleep and nap(s) are flexible and can be moved around to a degree to ensure circadian rhythm is preserved.

- Adaptation difficulty: Very easy

- Ideal scheduling: Consistent dark period everyday, core sleep starts 1-2 hours after dark period. Nap during daytime, no later than 6 PM.

- Former schedule name: Prototype X, Experimental X

This schedule differentiates itself from other established biphasic patterns on the site. X denotes any varying nap durations that one can take from day to day.

Mechanics

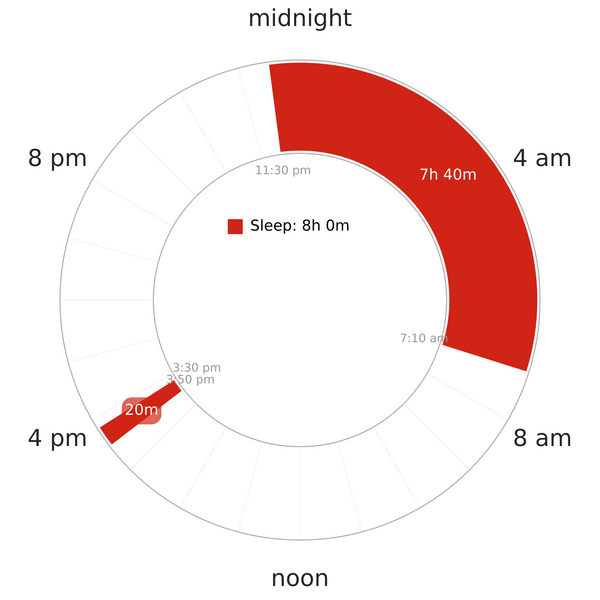

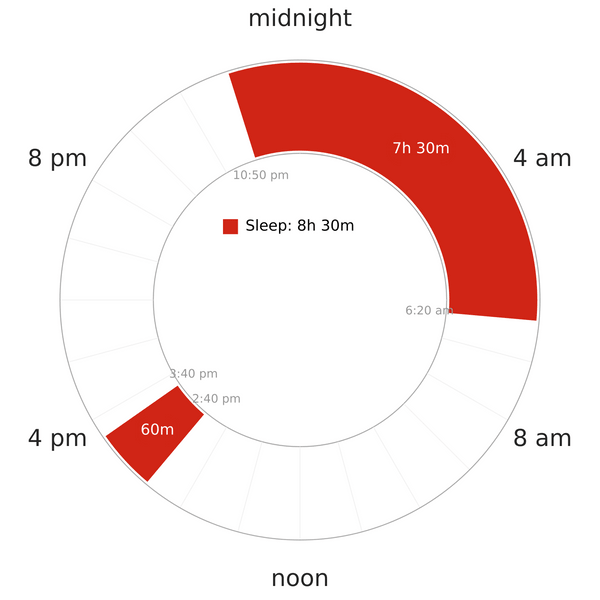

This flexible Biphasic schedule contains 2 sleeps per day (for the vast majority of days) without reducing the total time spent in bed.

- For example, a person who needs 8 hours of sleep each day can have a 6 hour core sleep at night and 2 hour siesta during the day. It has a lot of variations and flexibility in scheduling and has actually been done in the past in a way or another. For example, the experimenters reported certain positive results3 – sleeping 4 hours at night and 2 hours during the day (resembling Siesta), or 2 4-hour blocks (resembling Segmented sleep) was tested; results were shown to be positive short-term.

- Regarding daily lifestyle, many may find themselves naturally biphasic sleepers with a main core sleep at night that covers most or all of their SWS and REM need, complemented with a nap of varying lengths during the day depending on how sleepy they are.

People come to polyphasic sleeping and attempt other sleep-reducing schedules mostly to gain more wake time each day. Unfortunately, not many pay attention to the viability of non-reducing schedules.

- Thus, there have been few official attempts for this schedule that sleepers have fully logged and reported up to date. All of the experiences are at least somewhat positive.

- However, the inability to reduce sleep time holds back non-reducing schedules.

- Regardless, Biphasic-X has the potential to naturally reduce a tiny amount of total sleep each day with entrained biphasic sleeping and dark period; this theory still requires a big enough sample size to confirm if some sleep reduction is possible.

Daytime napping

This schedule applies most of the fundamental concepts of polyphasic sleeping while having flexibility of its own.

- Most days contain 2 sleep blocks, with the main core sleep at night sustaining wakefulness for a long period of time while having added benefits of a nap during the day for a quick refresh.

- Short nap lengths (> 10 minutes and < ~25-30 minutes) contain only light sleep to sustain wakefulness into later times of the day. Longer sleep blocks (> 60 minutes) do contain both SWS and REM. Although there is no REM sleep in short naps, being able to fall asleep and getting some NREM2 is still beneficial for some recovery effect and aid in memory and learning with alertness boost.

- On days when there is an earlier natural wake than usual from the core (~1h) and the sleeper cannot go back to sleep, it is then wiser to get up and start the day. When nap time arrives, the nap duration can then increase, up to 2h (resembling Siesta daytime core) to compensate for the earlier wake than usual in the morning.

- If core duration is already close to personal monophasic baseline, then the nap will automatically shorten (resembling E1 naps). On this schedule, there is no requirement to stick to any nap durations. They can last anywhere from 10m to 2h depending on day. The current level of homeostatic pressure before the daytime sleep also dictates nap duration.

Nocturnal Core Sleep

- Night sleep is the primary focus for health benefits; a daytime nap fits into the circadian rhythm of natural energy dip in the afternoon or around noon. It also favors people who cannot nap at the same time everyday.

- The ideal setup would be having a fixed core length at night and a fixed time of when to nap. Sleep times should be as consistent as possible. However, sleep times can be different on a daily basis if necessary as well.

- It is possible to do Segmented form some days. One would wake up in the night, and then place the second core much later than usual. This serves to wake up near the busy wake periods that do not allow any naps. If one wakes up in the middle of the night and can’t go back to sleep, they can also stay up for some time and wait for the second core.

- A consistent daily dark period stabilizes the circadian rhythm, starting at the same time everyday. Currently, there are a couple polyphasic sleepers in the community who stay on this schedule for extra flexibility. At the same time, they also learn to nap and recharge from a nap during the daytime; they also reported to have very few issues with the schedule. There is no nap past ~6 PM to facilitate falling asleep at night.

- During recovery days to recover from lost sleep or sickness, it is also necessary to have night sleep placed after dark period has started some time like normal days. This is to avoid messing up dark period and night sleep timing. If dark period for example is set at 10 PM, place the night sleep at no earlier than 11 PM for all days regardless of sickness.

Lifestyle

- Busier days allow for some sleep reduction in the main core sleep; additionally, more than one nap can be added to the schedule to maintain alertness level.

- This would detach from Biphasic form and become different polyphasic forms such as E2, E3, etc. This should be done only on very few occasions.

- As a result of this, some following days are recovery mode for extra sleep. Either lengthening the nap or the core sleep (maintaining Biphasic form) is acceptable.

- This mechanic is possible because of the non-reducing behavior. It is similar to monophasic sleepers who sleep less on certain days to gain time to fulfill extra commitments before recovering.

- The schedule fits most normal lifestyles that welcome taking a nap during daytime.

- Sleepers can also learn to nap to later transition into other reducing schedules with the napping habits.

Post-adaptation

With enough time and certain consistency in sleeping twice per day, ideally the sleeper will become accustomed to biphasic sleeping.

- They would be able to wake up from both the core sleep and daytime nap without using any alarms, even with different sleep times each day.

- In addition, they would not mess up night sleep or affect quality of the daytime nap.

- Total sleep time will also become consistent with only small variations from day to day.

NOTE: Biphasic-X is not to be confused with Random Biphasic where a sleeper would sleep twice everyday whenever they want, without any regards for circadian rhythm. This is ill-advised and should not be attempted.

The first detailed report as proof that this schedule works in the long term can be found here (45 days)4. A follow-up (~20 days after the first report) is here.

OTHER NON-REDUCING BIPHASIC SCHEDULES

These schedules fit the underage group, who need more sleep than adults, or those who prefer consistent sleep times.

- They have consistent nap and core durations everyday.

- Beginners should follow sleep times of these schedules strictly everyday for optimal sleep quality.

- Adaptation on these schedules go through 4 stages like other reducing schedules; however, adaptation difficulty is much milder due to a high total sleep time.

- Note that these schedules are based on the total sleep time in individual monophasic sleep duration. If your personal total sleep is higher than the numbers of the schedules above, then these biphasic schedules should add more sleep.

- After adaptation, one can flex the core sleep without much difficulty.

- Heavy exercising is also tolerable without needing extra sleep.

The differences between these specific biphasic schedules and Biphasic-X are:

- These schedules are consistent and keep their forms through everyday. If E1-extended is the schedule of choice, then the sleeper will follow that protocol and consistency for everyday. This includes a long core sleep at night and a short nap (10-30m) by default.

- Biphasic-X can contain purely 20m naps, or any other nap durations that suit personal need and situations (e.g, 15m, or 10m naps if nap duration has to reduce on certain days).

NON-REDUCING POLYPHASIC SLEEP

Triphasic-extended

Quad Core 0-modified

In this category, there are more than 2 sleeps per day on a regular basis with strict sleep times. This is to differentiate from Random sleep in the next section.

- These schedules have a major downside of requiring more than two sleeps per day without reducing total sleep time, which is one of the biggest perks of polyphasic sleeping.

- It is also much harder to accommodate the necessary lifestyles to afford these sleeping patterns with a lot of sleep distributed throughout the day; it is however possible to pull off in some cases.

- A true adaptation to these schedules is also necessary, making it another big con.

Sleep architecture is different by a large margin compared to monophasic sleep, so the body needs time to learn to sleep in shorter chunks to finally be able to wake up without any alarm support.

However, the adaptation process is for the most part a lot easier than the traditional versions (e.g, 4.5-hour Triphasic), thanks to a high total sleep. Eventually, repartitioning and sleep compression will be completed in each sleep.

The general argument as to why such schedules can be more effective than monophasic sleep is that the sleeper has more chance to experience vivid dreams with shorter sleeps once adapted and allow more room for heavy physical exercise with the extra sleep for recovery.

RANDOM

- Proposed by: N/A

- Total sleep: As much as you need

- Classification: Flexible, Non-reducing Polyphasic/Monophasic Sleep

- Specification: N/A

- Mechanics: Unlimited flexibility, sleep whenever tired, whatever nap or core length until auto-wake or alarm. Dark period, BRAC or circadian rhythm application are optional. No sleep for a day or two then sleep a lot more than usual afterwards is possible.

- Adaptation difficulty: N/A

- Ideal scheduling: Sleep whenever feeling tired enough, some days or all days can be polyphasic with at least 2 sleeps or monophasic with random added naps on certain days

Mechanics

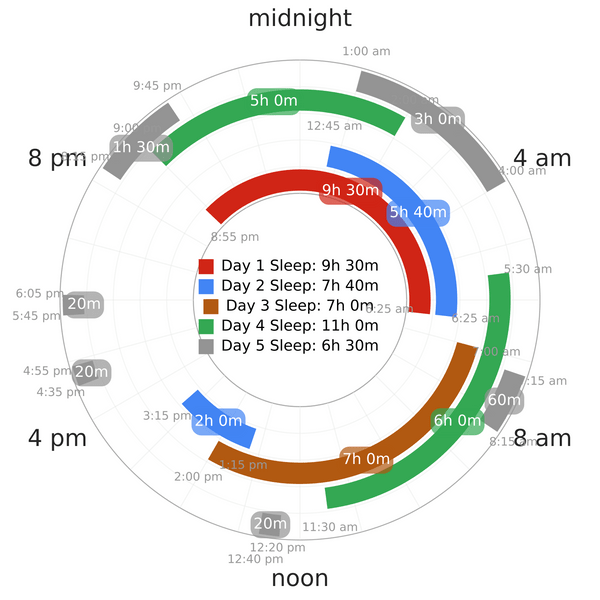

This schedule consists of any polyphasic schedules or subpatterns that do not reduce total sleep while impossible to be categorized into any current specific sleep patterns. This type of polyphasic sleep has been documented in one study3. However, in that study, the investigated sleepers were those who slept and woke up after short periods of time (coined as Random-living schedule by Claudio Stampi); they also slept at unusual times during the day, which is a rarer Random variant of sleeping with multiple short core sleeps (~2h).

Random denotes sleeping whenever tired, regardless of core or nap lengths and can be done at any time during the day. Usually, Random consists of monophasic sleep at irregular times, and sometimes adding additional nap(s) or core(s) at irregular hours.

- Lifestyles that benefit from completely random schedules are extremely busy/motivated career professionals, work shift rotations and constant travelling or work that demands continuous changes in sleep times.

- Sleep times are barely ever consistent and the daily activities are barely consistent either. Meal times, sleep-wake times vary on a daily basis.

- However, to a less extreme extent, Random can be made more consistent with a monophasic schedule on some days (more consistent sleep times), and some kind of Biphasic or polyphasic schedule for a couple other days (adding naps during the day when necessary).

Warnings

It is not recommended to pursue this kind of sleep, even with the infinite flexibility it provides.

- It usually ignores the basic principles of good sleep and sleep hygiene practices; these sleepers are usually not invested into preparing for their sleep (e.g, dark period is inconvenient if sleep times are rotated in a completely chaotic manner everyday).

- The concept of night and day can eventually become indistinguishable.

As a result, too much disturbance in circadian rhythm will develop and can lead to breast cancer5 and circadian rhythm disorder as a result of symptoms akin to shift work or jet-lag types.

- This in return causes insomnia, more interrupted sleep when sleeping at unusual times and poor quality sleep as the body is confused by the extreme changes in sleep-wake hours6.

- Having irregular sleep times and meal times also randomizes Zeitgebers (circadian rhythm cues), likely turns the overall sleep schedule into a free-running type (non-24h circadian rhythm)7

- Random sleep can also cause free-running disorder.

- More importantly, it is worth noting that irregular sleep-wake cycles can potentially lead to poorer academic performances due to the delay in bedtime. This can then clash with class times, resulting in constant daytime sleepiness, lack of productivity and possible memory problems even when sleep reduction is absent8.

There are better polyphasic sleep schedules to attempt than Random sleep; they have more consistency, more adaptation success chance and better sleep quality.

COMPARISON between NON-REDUCING and REDUCING POLYPHASIC SCHEDULES

Non-reducing schedules

Strengths

- More flexibility to move sleep around without directly hurting the adaptation process.

- Safe for underage. These individuals are still growing and need more sleep than adults, so non-reducing schedules (mostly Biphasic sleep) are safer choices if sleep times are consistent enough.

- Easier adaptation. It takes longer to reach the adapted state; however, the progress also induces much fewer adaptation symptoms since there is little to no sleep reduction that triggers the body’s reactions to sleep deprivation cues. Cognitive and physical performance during adaptation should remain intact.

- More productivity during the daytime and a more proactive lifestyle (more heavy sports, more social time, alertness boost from entrained napping habits).

- Resistant to travelling. Sleep times can adjust along these events accordingly (Biphasic-X/adapted E1/Siesta-extended). Short-term travelling (1-2 days) don’t usually pose big issues. In-progress adaptation can still be set back, but to a lesser degree.

- Resistant to sickness. Total sleep will automatically return to the previous healthy state when the body has fully recovered. Adapters will likely not need to use extensive alarm setups like on reducing sleep schedules. Adaptation can resume and is less affected than reducing sleep schedules.

Weaknesses

- Potential downside (1): Depending on personal goals, it may or may not be optimal to attempt to adapt to a non-reducing sleep schedule because it does not offer the extra waking hours, which is one of the most tempting premises of polyphasic sleeping.

- Potential downside (2): Sleep repartitioning is not as much as on other polyphasic schedules. This can in return lower the chance to recall dreams. However, schedules with a core sleep around sunrise hours will still likely increase dream recall opportunities.

- Potential downside (3): Sleep onset is also likely longer compared to that of reducing sleep schedules. This is because of the lower sleep pressure overall (e.g, it is common to fall asleep on E3 much faster than monophasic or E1). Therefore, falling asleep in naps can get more difficult and short naps are usually much lighter.

Conclusively, non-reducing schedules are likely safe long-term (except completely random schedules), thanks to the preservation of all sleep stages.

Reducing Sleep Schedules

Strengths

- More waking hours per day.

- Better energy, productivity and sleep quality once adapted.

- Vivid/Lucid dreaming. These schedules also promise more vivid dreams with REM naps, more chances to recall dreams to great details and much deeper sleeps thanks to repartitioning with a higher % of SWS and REM sleep and lower % of light sleep in all sleeps.

- Flexibility after adaptation. Sleepers can learn to move sleep around without hurting or reversing the adaptation process after the body has gotten used to the pattern. This helps keep the structure and total sleep without hurting sleep quality. However, this requires a certain amount of time “adapting” to flexing with different sleep times each day. Flexibility is also more limited for extreme schedules.

Weaknesses

- Potential downside (1): A strict adaptation regime is required for the body to learn to get in REM and SWS into different sleeps as total sleep reduces.

- Moving sleeps around during adaptation will only lead to failures; this is because sleep architecture is unstable.

- In addition, the body fails to recognize sleep times. Thus, it is necessary to plan ahead different important events in life if one attempts to adapt to a reducing sleep schedule.

- Adaptation can also be very difficult depending on schedules and other individual factors.

- Potential downside (2): Reversed adaptation. Extreme events that force skipping certain sleeps entirely or sickness for a couple days can reset the adapted state. This would eventually revert sleepers back to the previous sleep deprived stage.

CONCLUSION

It is common that sleepers want to gain extra hours awake each day by attempting polyphasic sleep; however, sometimes it is wiser to consider personal lifestyles thoroughly to determine the necessity of an adaptation process. A more stable and fairly consistent non-reducing biphasic pattern can be more beneficial if it is impossible to predict any life events during the first adaptation weeks.

- Being unable to finish adapting to a polyphasic pattern can be very damaging to productivity, cognitive functions and overall well-being. Sleep deprivation will wreak havoc on all fronts of well-being.

- During exams or stressful events, it is also better to avoid reducing total sleep time entirely. The debilitating effects of sleep deprivation will make things worse.

- One can start a non-reducing polyphasic schedule anytime without much consequence.

- A lack of motivation to stay awake more each day can justify a non-reducing sleep pattern to improve overall sleep structure. Lacking motivation to wake up will make adaptation a lot harder than it needs to be.

- While total sleep does not reduce, it is still worth considering a non-reducing biphasic pattern. When daily napping routine grows to be consistent, the combination of a restful core sleep at night and a good daytime nap can outperform monophasic sleep in terms of regulating productivity and generating energy.

To fully take advantage of polyphasic sleeping, non-reducing sleep schedules are only a last resort option to aim for more effective sleep other than monophasic sleep. Being able to sleep less and adapt to other schedules will give both extra wake time and productivity if the adaptation process can be completed. As a result, sleep-reducing schedules are still more appealing options.

Main author: GeneralNguyen

Page last updated: 3 April 2021

Reference

- Ekirch, A. Roger. “Segmented Sleep in Preindustrial Societies.” Sleep. 2016;39(3):715–716. [PubMed]

- Sleep Patterns of Medical Students; their Relationship with Academic Performance: A Cross Sectional Survey – Virtual Health Sciences Library. Accessed 14 Feb. 2020. [PubMed]

- Stampi, Claudio. “The Effects of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep Schedules.” Why We Nap, 1992, pp. 137–179, link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4757-2210-9_10,10.1007/978-1-4757-2210-9_10. Accessed 23 May 2019.

- “r/Polyphasic – OFFICIAL: The Perpetual Polyphasic Schedule! Final Report & A Comprehensive Guide for a Flexible Napping Lifestyle.” Reddit. Accessed 14 Feb. 2020.

- Keith, L. G., et al. “Circadian Rhythm Chaos: A New Breast Cancer Marker.” International Journal of Fertility and Women’s Medicine. 2001;46(5):238–247. [PubMed]

- Sack, Robert L., et al. “Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders: Part I, Basic Principles, Shift Work and Jet Lag Disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Review.” 2007;30(11):1460–1483. [PubMed]

- Stampi, Claudio. Why We Nap : Evolution, Chronobiology, and Functions of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep. Birkhauser, 2014.

- Phillips, Andrew J. K., et al. “Irregular Sleep/Wake Patterns Are Associated with Poorer Academic Performance and Delayed Circadian and Sleep/Wake Timing.” Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1). doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03171-4.

- “r/Polyphasic – The Beauty of Biphasic Sleeping: After 7 Months.” Reddit. Accessed 14 Feb. 2020.