Introduction

Daydreaming, also known as mind wandering, is a common phenomenon in daily life. Under normal conditions, it is usually harmless. It is usually moments of distraction from current tasks, similar to lost-in-thought moments. In sum, it is “a wide variety of spontaneous and undirected mentation”. Most notably, it can account for up to 30-50% of thought-probe responses in laboratory and field studies1.

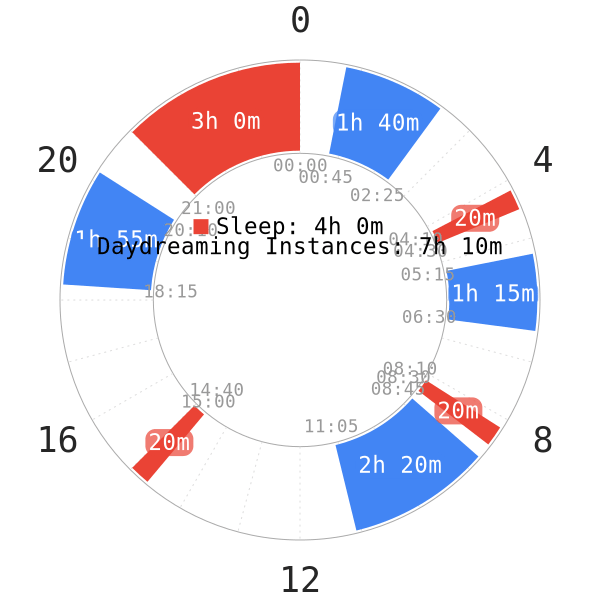

There appears to be some reciprocal correlation between the frequency of daydreaming and sleep quality, and even chronotype; however, it is still unclear how much sleep deprivation can affect the frequency of daydreaming. On the other hand, whether daydreaming in return causes sleep deprivation (insomnia) is also unclear1. However, in extreme cases, daydreaming can interfere with daily life on a global scale.

In polyphasic sleep adaptations, daydreaming anecdotally appears to be a controllable threat; however, sleep deprivation effects seem to amplify it and can cause irritating experiences. Whether daydreaming is a direct product of sleep deprivation remains inconclusive. There are also ways to overcome excessive daydreaming, depending how much it affects each individual.

Even though daydreaming is far from as malevolent as other well-known sleep disorders (e.g, sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome), polyphasic sleepers still experience it rather often.

Daydreaming, sleep quality and sleep deprivation

Sleep Quality

A reliable yet moderate correlation has been found between daydreaming and sleep quality. The poorer the sleep quality, the more frequent daydreaming occurs1. Another study also claimed that daydreaming can also affect sleep quality by increasing sleep onset latency2. Despite limitations from the study, it is reasonable to establish such correlations.

Being distracted and lost in continuous thoughts can effectively prevent sleepers from entering sleep. Examples include:

- Rolling around in bed

- Inability to sleep due to a racing heart

- Especially stress or anxiety contribute to nocturnal insomnia.

As a result, sleepers become unable to stop the train of thoughts and cannot commit to sleeping.

Similarly, in polyphasic sleeping, stress responses are also frequently reported. However, this is more so in the case of new nappers and novice polyphasic sleepers.

- On reducing sleep schedules with multiple naps, a few beginners can develop the fear of not being able to fall asleep in naps. This sleep deficit may then contribute to their oversleep in the next session. This is a legitimate concern.

- If these sleepers find out they have little time left to cool down for a nap or core, they may also panic.

Sleep Deprivation

Poor sleep quality includes sleep disturbances. Examples are:

- Waking up in the middle of the night and cannot fall asleep again.

- Long sleep onset latency.

- Waking up in the wrong sleep stages.

- Feeling unrested upon awakening despite a full night’s rest . This may be a result of not preventing blue lights before sleep, delayed sleep phase, desynchronized circadian rhythm, etc.

There has been a relationship found between daydreaming frequency and sleep deprivation. Typically, the more sleep debt, the more daydreaming later on3. This is applicable to polyphasic sleeping adaptations as well.

- Adaptations to extreme schedules (anywhere below 5 hours of total sleep) become hard for the majority of adapters. They also cost a lot of productivity hours. For example, a lot of efforts dedicate towards just trying to stay awake, inability to focus on current tasks or staring at the clocks for time to pass).

- Due to certain levels of cognitive impairment with some sleep reduction, daydreaming just increases adaptation difficulty overall. It can be a very powerful disruptor against personal productivity, especially during Stage 3 of adaptation.

Daydreaming and chronotypes

Interestingly enough, sleep chronotypes appear to play some role in daydreaming frequency. However, all relevant data stems from studies on monophasic sleep. These studies focus was on cognitive performance and the state of mind wandering. The conclusions as as follows:

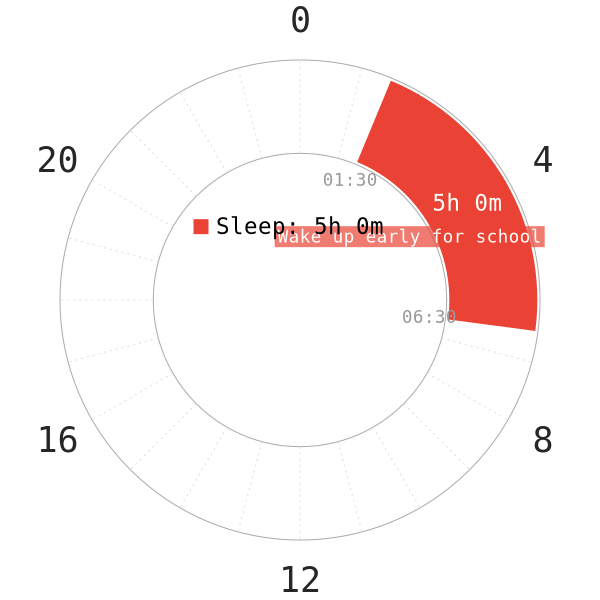

- Delayed sleep phase (Wolf chronotype) generates more daydreaming occurrences.

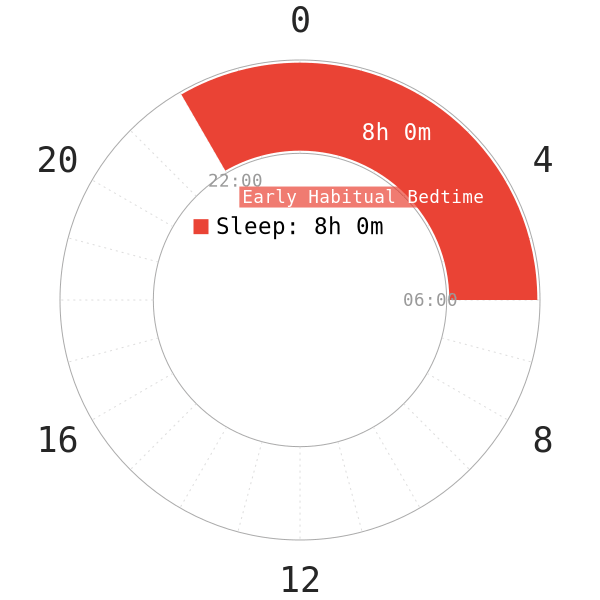

- Early sleep (Lion chronotype) has a positive correlation with mindfulness and alertness1.

- The explanation for this connection is that Wolves are likely have to wake up earlier than scheduled for different personal reasons, This potentially causes them to be sleep deprived (e.g, work, school).

Patterns of occurrence

It is also worth noting that circadian dips from different chronotypes can influence daydreaming occurrences. One study demonstrated that preferred mentally active hours in the day can have an effect on dispelling or reducing daydreaming or mind wandering instances7. However, the study utilized a retrospective questionnaire method for participants; the data might not be as accurate.

- During these hours, these individuals report to be more alert and focused than non-preferred hours, possibly because of their daily routines.

- As a result, non-preferred hours stimulate more daydreaming (e.g, evening hours for morning type or morning hours for evening type).

- Hypothetically, daydreaming occurs at hours where spontaneous thoughts take control over executive control during non-preferred hours of the day. During these hours, the brain goes into default mode, which is akin to rest or autonomic mode in response to external cues and stimuli.

Since polyphasic sleeping is pretty much about consistency and maintenance of sleep-wake hours strictly, the body gets used to the waking hours eventually. Adapted sleepers then get accustomed to total sleep time each day and alertness dips patterns. When a stable sleep-wake polyphasic schedule becomes a routine, sleepers feel rested and can minimize daydreaming.

At this point, they can live with it without fearing productivity lapses.

How dangerous can daydreaming get?

There is some discrepancy between daydreaming experience reports.

- One demonstrated that daydreaming affects each individual depending on how positive the experience itself is. If it is something positive, it can improve emotions and reduce loneliness3,8.

- On the other hand, negative, repetitive and self-focused daydreaming incidents result in worse emotional health and even some psychological issues (e.g, dissociative tendencies, mood disorder)3.

- In severe cases, excessive, uncontrollable daydreaming can eventually lead to maladaptive daydreaming (MD), or daydreaming disorder4,5. MD can become so transparent that patients often mix up fantasy and reality. For example, imagining having a conversation with a superhero in comics5,6.

- Furthermore, there is also high comorbidity of MD. In one study, approximately 75% of the total number of patients (39) qualified for at least 3 additional disorders. About 41% met criteria for at least 45.

Despite the crippling effects of MD, there has been no self-report on such disorders in the polyphasic community up to date.

Methods to alleviate daydreaming

During polyphasic sleep adaptations, daydreaming is inevitable. The only main concern is productivity during waking hours, which is one of the main perks of polyphasic sleeping. To be able to remain mentally active, consider the following:

- Set up a long list of activities to fill up the waking hours.

- Depending on the polyphasic pattern of choice, staying alert may or may not be difficult for the sleeper.

- One of the most important factors is motivation. Without any motivation to stay awake and do useful activities, adaptation will quickly become immensely difficult.

- Many polyphasic sleepers have succeeded in adapting to multiple different sleep schedules thanks to sky-high personal motivation. They report to continuously stay engaged with their favorite activities. Check out the following post, How to Manage Sleep Deprivation for more information.

Even after the adaptation phase, daydreaming can still occur from time to time. However, its effects are largely negligible and do not interfere with daily performance. Getting the right amount of sleep is what can dictate the patterns of daydreaming. Completing a polyphasic adaptation and staying away from sleep deprivation is a healthy lifestyle.

Conclusion

Daydreaming usually is benign in the context of polyphasic sleeping. It can both affect sleep quality when a sleeper first begins sleeping polyphasically. This is a result from sleep deprivation at the same time from the sleep pattern of choice. Additionally, the intensity of daydreaming varies between individuals and depends on which schedule sleepers are attempting.

Understanding and determining personal chronotypes can give more insights on how to form routines and stick with them for long term. Most importantly, staying motivated throughout adaptation is the key to adapting and making use of sleep-wake hours wisely.

Main author: GeneralNguyen

Page last updated: 2 April 2021

Reference

- Carciofo, R., Du, F., Song, N., & Zhang, K. (2014). Mind Wandering, Sleep Quality, Affect and Chronotype: An Exploratory Study. PLoS ONE, 9(3), e91285. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091285. [PubMed]

- Harvey, A. G., & Payne, S. (2002). The management of unwanted pre-sleep thoughts in insomnia: distraction with imagery versus general distraction. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(3), 267–277. doi:10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00012-2. [PubMed]

- Poerio, G. L., Kellett, S., & Totterdell, P. (2016). Tracking Potentiating States of Dissociation: An Intensive Clinical Case Study of Sleep, Daydreaming, Mood, and Depersonalization/Derealization. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01231. [PubMed]

- Bigelsen, J., Lehrfeld, J. M., Jopp, D. S., & Somer, E. (2016). Maladaptive daydreaming: Evidence for an under-researched mental health disorder. Consciousness and Cognition, 42, 254–266. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2016.03.017. [PubMed]

- Somer, E., Soffer-Dudek, N., & Ross, C. A. (2017). The Comorbidity of Daydreaming Disorder (Maladaptive Daydreaming). The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 205(7), 525–530. doi:10.1097/nmd.0000000000000685. [PubMed]

- Giesbrecht, T., & Merckelbach, H. (2006). Dreaming to reduce fantasy? – Fantasy proneness, dissociation, and subjective sleep experiences. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(4), 697–706. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.02.015

- Carciofo, R., Du, F., Song, N., & Zhang, K. (2013). Chronotype and time-of-day correlates of mind wandering and related phenomena. Biological Rhythm Research, 45(1), 37–49. doi:10.1080/09291016.2013.790651

- Poerio, G. L., et al. “Mind-Wandering and Negative Mood: Does One Thing Really Lead to Another?” Consciousness and Cognition. 2013;22(1):1412–1421. [PubMed]